Construction of the Royal Inland Hospital. Mrs. Thomas Whitmore photograph collection

RECOVERY DRIVE: COMMUNITY WELLNESS IN KAMLOOPS

January 2, 2021 – September 4, 2021

In response to the Covid–19 pandemic, the KMA cancelled all existing programming and bore down quickly to create a way to place the local impact of the virus in an historical context. The exhibition included local initiatives and the voices of front-line health care workers set against a backdrop of complementary models for wellness in the community: Royal Inland Hospital and the Tranquille Sanatorium. For the purposes of privacy, only the historic components have been included here.

Royal Inland Hospital

In the early 1880s Kamloops was a growing population centre in need of a permanent medical facility.

To that point, the trading hub on the Thompson Rivers had been served only by traveling doctors and other medical professionals.

With the arrival of C.P.R. doctor Simon J. Tunstall in 1884, the movement lobbying for a permanent hospital found a voice. Along with treating regional employees of the Canadian Pacific Railway, Tunstall set up a private general practice and began lobbying for a permanent hospital. His efforts were bolstered by Michael Hagan, the owner of the Sentinel newspaper, so word and support quickly spread throughout the region. A hospital board was soon established to coordinate fundraising efforts, chaired by local businessman James McIntosh. Tunstall’s brother was made board secretary, with lawyer William Spinks acting as treasurer, along with a range of board members from communities in the region.

In 1885, a permanent hospital was built on the north side of Lorne Street at the foot of 3rd Avenue.

The hospital was described as a two-story wood frame building featuring a wraparound verandah on both levels, and 12 beds for patients. Dr. Tunstall was appointed the hospital’s first Medical Officer, while other doctors in Kamloops were also able to treat patients admitted to the new centre. Early staff were predominantly male, including nurses, who were led by William Christopher.

In a measure reflecting its stature and significance, in 1896, the medical facility was formally incorporated as the Royal Inland Hospital.

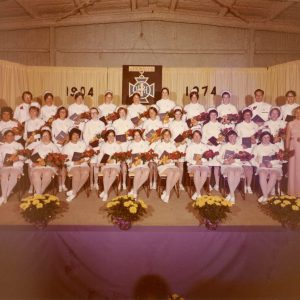

A Training School for Nurses was also established in 1904, led by the hospital’s second Matron: Jean Matheson. In 1907, Matheson resigned from her position and became the first Matron of the newly opened Tranquille Sanatorium.

In 1887, Dr. Edward Furrer replaced Dr. Tunstall, while Eleanor Potter became the hospital’s first Matron, after William Christopher resigned. The now–established hospital was already experiencing pressure from Kamloops’ continued population growth, and it quickly responded with a series of renovations in 1891, 1896, and 1901; as well as a plan for an isolation hospital to treat patients with infectious diseases.

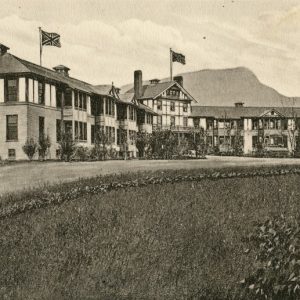

The new hospital was designed by Vancouver firm Birds and Blakemore, and local builders Johnson and Co. were given the contract to the construct the foundation.

Provincial Government and the City of Kamloops each gave $15,000 in support of the project, but community fundraising efforts led by groups such as the Ladies’ Auxiliary to the Royal In- land Hospital were crucial.

On June 23, 1911 the cornerstone for the building was laid by William Roper, and a year later construction was complete. The new Royal Inland Hospital officially opened September 14, 1912 in a ceremony conducted by the visiting Duke of Connaught. The facility held 110 beds, a considerable increase in the hospital’s capacity to care for the community.

During the first decade of the 1900s the hospital expanded further, with renovations to the Lorne Street site (notably the Trafalgar Wing, completed in 1905), the construction of an isolation hospital at Mission Flats, and a home for the hospital’s nursing staff. These additions, however, could not keep up with ever-growing demand and, by 1909 a second isolation hospital was built on Columbia Street.

When a parcel of nearby land was granted by the Provincial Government, planning for an expanded hospital complex began.

Unfortunately, even the bigger hospital was not able to handle the arrival of the Spanish Flu in 1918.

With the hospital at capacity, the army barracks and the old Patricia Hotel were commandeered to accommodate an overflow of patients. The following two years saw over 600 patients treated for the Spanish Flu in Kamloops, prompting another call to—expand— but as the pandemic eased the hospital did not increase in size.

The 1920s were a prosperous time for the Kamloops community, and the hospital was able to grow in turn. New improvements and renovations were made to the buildings and a new nurses’ home was built to house the growing number of trainees at the nurses’s training school. 1929 also saw the appointment of the hospital’s first general manager, S.M. Cosier. Cosier took on the complicated administration and business needs of the hospital, which had formerly been carried out by a volunteer board.

During the Depression, the fortunes of the hospital mirrored the fortunes of the community. By 1933 the Royal Inland Hospital faced bankruptcy.

The community rallied to raise funds and, with some limits to its services, the hospital continued to operate.

In 1934 the RIH introduced a regular insurance plan, charging $1 per day to subscribers who would receive free treatment if and when it was needed. The initiative provided steady funds for the hospital and reduced costs for patients.

The City of Kamloops, too, increased its involvement, taking over and improving the ambulance service, which had previously been operated independently.

The 1940s saw the hospital in prosperity once again, with approval for a major addition passed in 1944.

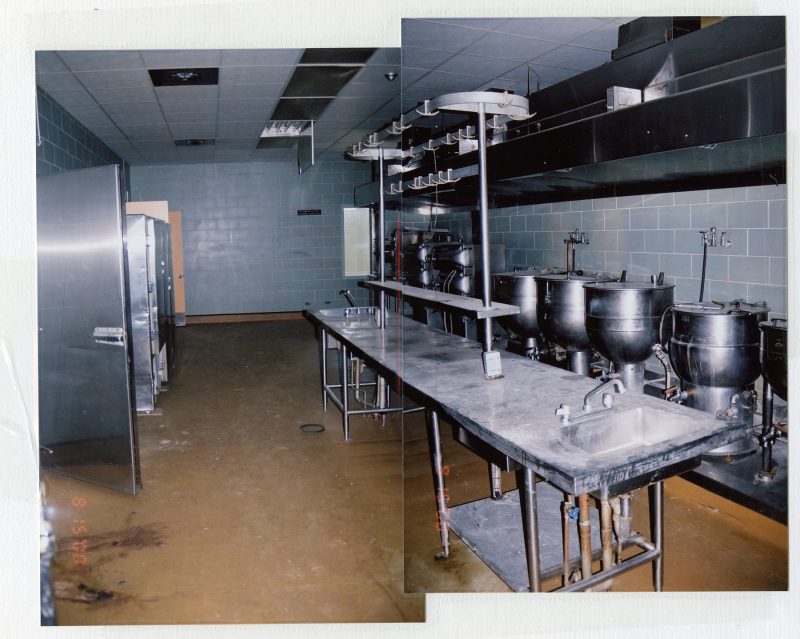

This new addition would not be completed until 1947, but would double the hospital’s bed capacity and see the addition of two new wings. The wings contained operating rooms, a central supply, patient rooms and wards, a maternity ward, along with a dining room and kitchen.

In 1948 a new Hospital Insurance Service plan was passed in provincial legislation, providing more funds to hospitals through the collection of payroll-deducted premiums and broadening the scope of medical coverage for patients.

The Royal Inland Hospital continued to operate well through the 1950s, receiving accreditation for their services in 1956. A new addition began to be planned by the middle of the decade, but efforts to begin construction would not break ground until 1961 under the leadership of Phil Gaglardi.

1971 saw the last intake of nursing students for the Nurses’ Training School, with the class graduating in 1974.

Responsibility for this valuable training program shifted to

Cariboo College (later University College of the Cariboo and currently Thompson River’s University. Many nurses continued to work at the hospital to gain practical experience and qualifications.

The buildings that had previously housed the Training School and dormitories were renovated into a psychiatric unit and a patient self-care unit.

By the late 1970s the hospital was once again looking to expand, and major construction continued throughout the next decade.

The original 1911 main core of the hospital complex was demolished and replaced with a 7-storey tower and an additional 4-story west wing. These new buildings contained an intensive care unit, maternity ward and nursery, a rehabilitation ward, an ambulatory care unit, a renal unit, EEG support services, additional patient wards, a vascular lab, and an orthopedic clinic.

During the following two decades, the RIH underwent few outward changes. However, quiet improvements to services, new technologies, expanded care facilities, and interior work continued to bolster the well-established facility.

One notable project was the development and construction of a new psychiatric facility known as Hillside Centre. The new facility, nestled into the hills of Peterson Creek Park south of the main hospital complex, was opened in February 2006 and continues to focus on psychiatric health and rehabilitation services.

2012 saw the 100 year anniversary of the Royal Inland Hospital at Columbia Street.

The occasion was marked with an announcement early in the year of another major expansion of the hospital complex: a new Clinical Services Building. With a focus on outpatient services, the project served to lay the groundwork for a reimagined hospital complex that would continue to be developed.

The new CSB was built by Bird Construction, and was completed in 2016. The dramatic structure abuts onto Columbia Street, and significantly alters the entrance to the hospital complex, which had been characterized by rolling fields since 1912.

The Royal Inland Hospital still operates today at their much-expanded Columbia Street location, offering core physician specialties, 24-hour emergency and trauma services, ambulatory and outpatient clinics, and diagnostic services. Specialty services include ambulatory psychiatry, elderly mental health, clinical nutrition, and lung health. Their most recent expansion project is a new patient care tower, under construction since 2018.

![KMA Photo 10428: The hospital expansion, showing the new and old residences, [November 28, 1985].](https://www.kamloopsmuseum.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/31.KMAPhoto_10428.jpg)

Tranquille Sanatorium

Tuberculosis, or “consumption”, is a bacterial infection that largely affects the lungs, causing chest pain, a cough that brings up blood and sputum, fever, and weight loss.

It is passed similarly to a cold or the flu, largely through the aerosolized droplets of a cough or sneeze, although it can also be transmitted by unpasteurized milk. As patients become more ill, the presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in their sputum in- creases, making it significantly more transmissible in advanced cases than mild ones. Throughout the nineteenth century, tuberculosis was regarded as the cause of death for one quarter of Europeans.

At the dawn of the twentieth century, the best treatment for tuberculosis was fresh air, rest, and good food. Sanatoriums, set in the right climate, were not only equipped to provide this “cure”, but they also acted as a way to isolate increasingly infectious patients from the general population. Wealthy Europeans had been making their way to the southern United States for decades, seeking the warmer, drier climate. The first sanatorium in Canada was opened in 1897 in the Muskoka region, north of Toronto.

In 1899, Dr. Charles Joseph Fagan was appointed Secretary to the Provincial Board of Health, and began advocating for measures that addressed the prevention and treatment of tuberculosis. Alongside increased education for medical staff and the population, Fagan sought to establish a dedicated sanatorium to treat these specialized patients.

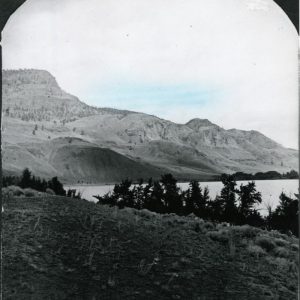

A site at Tranquille, near the city of Kamloops, was chosen by Fagan and the Anti-Tuberculosis Society. The climate in Kamloops lent itself well to the treatment of tuberculosis, and the Tranquille site especially so, given its southern exposure, shelter from northern winds, and access to the lake.

In fact, tuberculosis patients had already been accepted as boarders by William and Jane Fortune, the original owners of the 560-acre property, for some time. Although other properties were considered, the Fortune ranch was ultimately purchased for $57,000.

In 1907 the Tranquille Sanatorium was born. In the tradition of the times, the Tranquille Sanatorium was named the “King Edward Sanatorium” and was only the seventh sanatorium in Canada; and the first to open west of Ontario. The first medical superintendent was Dr. Robert W. Irving, who would remain in his position from 1907–1910. The first nursing Matron was Jean Matheson, who also remained until 1910.

The First World War, with its trench warfare, close quarters, and gas exposure, created a sharp increase in military admissions, accounting for 25% of admissions in 1918.

Of these, 10% would be discharged as not suffering from tuberculosis at all. Patients at Tranquille were usually young, with the largest demographic being ages 20-35.

Patients used cheesecloth handkerchiefs, which were burned when they finished with them, and could be thrown out of the sanatorium for disobeying the rules for “taking the cure”.

As patient numbers increased, so too did entertainment at Tranquille. Photographs reveal striking gardens and patient picnics at the lake. A five hole golf course was built in 1915, and a weekly moving picture show was established in the 1920s.

Occupational therapy afforded patients the opportunity to work with reeds, pine needs, and beads to create all manner of crafts for sale; as well as woodwork, including the building of a boat in 1925. The increase in applications by children propelled the construction of a school house.

As patient numbers increased, so too did entertainment at Tranquille. Photographs reveal striking gardens and patient picnics at the lake. A five hole golf course was built in 1915, and a weekly moving picture show was established in the 1920s.

Occupational therapy afforded patients the opportunity to work with reeds, pine needs, and beads to create all manner of crafts for sale; as well as woodwork, including the building of a boat in 1925. The increase in applications by children propelled the construction of a school house.

![KMA Photo 8613: Nurses and Dr. Vrooman, [ca. 1910-1918].](https://www.kamloopsmuseum.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/53.KMAPhoto_8613.jpg)

From the initial establishment of the Tranquille Sanatorium in 1907 it was argued that a second sanatorium for patients with advanced tuberculosis was desperately needed in the province.

From the outset, nearly half of the patients accepted at Tranquille were advanced cases of tuberculosis. The result of this was greater strain on nursing staff, longer stays and fewer discharge; along with long wait times that often meant less serious cases became advanced, due to lack of bed space and treatment. It was agreed, however, that taking in these advanced cases was a necessity, if only to isolate them from the rest of the community.

Considering the high number of advanced cases, the treatment at Tranquille was extremely successful. Patients typically gained a little over 10lbs, and 142 days was the average stay; although this increased to 333 days as time went on, with many advanced cases remaining for years.

The sanatorium continued to expand dramatically to 120 beds by 1916, 245 beds by 1921, and 360 beds by its closure in 1958.

The Tranquille Sanatorium was the site of cutting-edge research into tuberculosis treatment and many things that went along with it, such as nutrition for weight gain and blood testing for sexually transmitted disease.

Tuberculin, a variety of tuberculosis cultures that would eventually lead to the BCG vaccine, was used as early as 1909 for experimental treatment. A dentist was brought on as a permanent member of staff when the connection was made between chronic illness and dental health. A lab technician was hired in 1925 to work in collaboration with the National Research Council and other sanatoriums in Canada. In 1929, Medical Superintendent Dr. Lapp was one of thirty doctors in Canada sent to Rome for three months to participate in the International Union Against Tuberculosis. Patients were also treated with artificial pneumothorax and thoracoplasty, particularly as last resort treatments in advanced cases.

The 1940s-1950s brought antibiotics, new drug treatments, and a vaccine for tuberculosis. The disease declined rapidly, and fresh air, rest, and good food fell out of favour as treatment, leading to the closure of the Tranquille Sanatorium in 1958. Despite the sharp decline of tuberculosis in Canada in the mid-twentieth century, the disease has experienced a resurgence since the 1980s, exacerbated by the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the developing world. The World Health Organization notes that 161 member states continue to vaccinate infants with the BCG tuberculosis vaccine, and roughly 80% of children receive the vaccine, although its impact is limited. In Canada, the BCG vaccine continues to be used in rural communities with high tuberculosis rates. There is still no cure.

![KMA Photo 8688: Dr. Houle at Tranquille Sanatorium, [ca. 1918-1920].](https://www.kamloopsmuseum.ca/wp-content/uploads/elementor/thumbs/50.KMAPhoto_8688-qsyukc4rddyufg3olrxu38mcgx7mee3v27w1s6xl14.jpg)

![Gladys Isabella Groves fonds, 2017.003.001, page 14e: Dorothy and Phyllis Lincoln [staff], ca. 1940s.](https://www.kamloopsmuseum.ca/wp-content/uploads/elementor/thumbs/49.GIG_14e-qsyukc4rddyufg3olrxu38mcgx7mee3v27w1s6xl14.jpg)

![KMA Photo 8683: Vrooman family, [ca. 1910-1918].](https://www.kamloopsmuseum.ca/wp-content/uploads/elementor/thumbs/52.KMAPhoto_8683-qsyukc4rddyufg3olrxu38mcgx7mee3v27w1s6xl14.jpg)

The buildings at Tranquille were converted to the Tranquille Medical Institution, which was a home and school for patients with a variety of unique needs.

At its height, Tranquille housed roughly 700 people, or about a quarter of the province’s institutionalized population. As with the Tranquille Sanatorium, staff and their families lived onsite. Patients lived in wards housing 37-85 people.

Between 1971 and 1983, as care standards began to shift from merely custodial care to reintegration, more than four hundred patients from Tranquille were reintegrated into the community, replaced by new patients from other provincial institutions. In 1984, the Tranquille Medical Institution shut down as part of a national movement to reintegrate patients into communities. There was much protest around the closure, from parents, staff, and Kamloopsians.

In 2003, the provincial government offered a formal apology to victims of institutionalized abuse at four provincial institutions, including Tranquille. However, as of 2018, there have been no public claims of abuse at the Tranquille Medical Institution.

There have been several redevelopment plans for Tranquille, including a 1991 plan that renamed the property, Padova City.

In 2005, the Tranquille site was purchased by British Columbia Wilderness Tours, who proposed redevelopment in the form of the “Tranquille On the Lake Neighbourhood Plan.”

Currently, the site is being used by Tranquille Farm Fresh, which, in addition to working as an urban farm, offers heritage and Halloween tours of the Tranquille site, seeking to educate and engage visitors with its history.

-

Admission By Donation Suggested

$1 per child & $3 per adult.

Frequently Asked Questions -

Museum Hours

Tuesday - Saturday: 9:30am - 4:30pm

Sunday & Monday: Closed -

Archive Hours

Tuesday - Friday: 1:15pm - 4:00pm

Saturday: By Appointment

Sunday & Monday: Closed -

Please Note:

The admissions desk may ask that you check your bags and any food and beverages upon entry.

We encourage you talk in our galleries, have fun, and discuss the content and artifacts you see as you make your way around the building. Laugh, cry, and remember that we like hearing our galleries active!